Last month, for the first time ever, I entered a theatre – or, as I like to call it these days, the poor man’s football, seeing that, at £28, its dearest ticket is still a less expensive form of two hours’ entertainment than the cheapest ticket to watch the ‘People’s Game’ at the E*****s Stadium. It was to watch a play called ‘In Basildon’ at the Royal Court Theatre in Sloane Square (there’s something rather ironic about seeing the word ‘Basildon’ emblazoned in neon lights on a theatre in the middle of plush Sloane Square).

The play was a kind of kitchen-sink version of TOWIE, if you can imagine such a thing, and its story-line centred on a long-standing family feud with a 60-year-old Essex man called Ken on his death bed. Here, on its YouTube trailer, you can hear ‘Abide with Me’ as the theme tune, which is also the choice of music at Ken’s funeral, since it always brought a tear to his eye on Cup Final day. Though Ken, like many a modern Essex man, chose in his lifetime to cheer for ‘Wess Tam’ (his nearest and dearest, who included a Spurs fan, sang I’m Forever Blowing Bubbles as he passed from this mortal coil), it was actually a very different set of Essex men – in terms of social class and historical period – former Epping public schoolboys, The Wanderers, who first lifted the cup in 1872. The following year, the final was moved to a morning kick-off to avoid clashing with the Varsity Boat Race, as the defending holders played and beat Oxford University. Fast forward nearly fourteen decades on, however, and a switch of kick-off time for the FA Cup Final is pretty much just one among many footballing acts centred on a morbid death-bed scene for the football family’s own silver-coloured old friend with big ears.

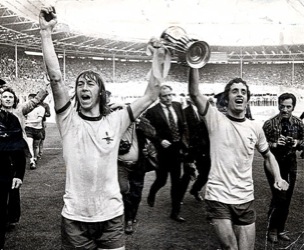

This Saturday at Wembley sees the 130th FA Cup Final. Not too long ago, this was deemed to be the climax to the footballing season. Not only was the idea of a full league-programme scheduled for the very same weekend unthinkable, the scheduling of anything on Grandstand or World of Sport not Cup Final-related for a good three hours prior to the kick-off was beyond the pale – except, of course, for a special pre-recorded Cup Final wrestling bout in the early afternoon which was ITV’s showcase bout for the year, usually involving a Big Daddy v Giant Haystack-style battle. The Final was shown on two of only three TV channels that existed back then – in the late 60s, it was even on all three, as it was shown in colour on BBC2, while BBC1 and ITV showed it in black and white. On Cup Final day, the game was quite literally inescapable.

There was no doubt that it was the highlight of the footballing year, and the winners of the FA Cup of any year would be remembered by many long after anyone could recall the winners of the league for the same season. If you don’t believe me, ask anyone about the Matthews Final and the Coronation Cup Final of 1953 – then ask them who won the league that very same year. Chances are they will struggle. It was actually the Arsenal, and nor was it a run-of-the-mill finish to the season either. At teatime the previous evening, Arsenal won the title after a nail-biting 3-2 victory over top-six side Burnley at Highbury, on the final league-fixture of the season, to win the title on goal-average by 0.09 of a goal. Prior to Anfield ’89, this was one of the closest finishes to a season ever. It was also history in the making, as Arsenal won a then-record seventh league title. You can see, however, from the archives from the news coverage the following morning on May 3rd 1953, , that in terms of column inches it was dwarfed by the build-up to the ‘Matthews’ Final, which was to take place later that day. Compare that then to last year, when many complained that Man City’s long 35-year wait for a trophy was overshadowed by Man Utd’s record-breaking 19th title just minutes before the kick-off of the FA Cup Final. It’s also worth noting that Matthews was presented with his medal in 1953 by the newly-crowned monarch. However, in her diamond jubilee year, the Cup Final is not deemed worthy of an appearance from any of the royals!

The fact of the matter is that the world, inside and outside of football, has changed. The FA Cup Final from 1958-1988 accounted for at least two-thirds of all programmes shown on English TV that Saturday afternoon – in an era with no alternative media such as the internet or DVDs, and for the most part no home VHS, as well as a limited number of radio stations too. The event had enormous social significance even to those apathetic to football. I still have painted rosettes from nursery class which I made especially for the Cup Final day of 1983 – which had Man Utd on one side and Brighton on the other. My sister, who is a few years older than me, had one with Man Utd on one side and the Arsenal on the other for the 1979 final. I don’t think either of us knew much of football at the age of four, but both had the importance of the occasion impressed on us. This was by no means a rare thing either – the front cover of John Lennon’s album ‘Walls and Bridges’ includes a picture drawn by an 11-year-old John , at school, of the 1952 FA Cup Final involving Arsenal and Newcastle. And John himself took no real interest in the beautiful game either as a child or as an adult.

Not only was it blanket coverage of this game that made it so important, it was also the lack of coverage for the rest of the nine months of the season. The Cup Final was the only domestic fixture viewed in its entirety all season. Now, it is just one fixture viewed among many on any given Saturday afternoon. In this respect, the FA Cup Final had a symbolism back then that it is never likely to see returned, simply because the world, technology and the media have moved on by leaps and bounds since those days. That said, the football authorities are certainly guilty of having failed to preserve its importance, even going so far as to actively destroy what the FA Cup once stood for. On Saturday tea-time, Liverpool will have a chance of achieving a domestic Cup double – an accolade that Arsenal were the first to achieve at the end of the inaugural Premiership season back in 1993 – in which we finished a lowly 10th. On our end of season video that year, the narrator Matthew Lorenzo opined that despite this: ‘every side above Arsenal, with the possible exception of (Premiership winners) Manchester United, would have swapped places to be in Arsenal’s shoes on Cup Final day’ – which of course was entirely true. When Liverpool themselves matched this feat as part of their Treble in 2001, it may well have been a point of argument whether Arsenal – who finished above them in second, but won nothing, would have swapped places if Liverpool hadn’t sealed a great season with qualification to the Champions League, which they did by clinching the third-place spot on the final game of the season.

In 2012, however, it would probably take an extremely one-eyed Liverpool supporter to claim that either Spurs or Arsenal would swap places with them this Saturday rather than be in the running to achieve that sought-after third place spot and the automatic entry to the Champions League that comes with it. It is, to be frank, an utterly surreal state of affairs that a side that could walk away with both domestic trophies would end up feeling envious of a side that finished the season trophy-less in third or fourth spot in the league. It is, however, a footballing reality in 2012. Chelsea also may well be looking at Saturday teatime as an unwanted distraction, with one eye on Munich in two weeks’ time. One wonders whether, deep down, if they could emulate Liverpool’s and Everton’s moving of the meaningless ScreenSport Super Cup Final of 1986 to the following September to concentrate on more important end-of-season matters, they would do exactly the same with this year’s FA Cup Final, because winning it would mean absolutely nothing to them in the big scheme of things.

This harsh appraisal of what the FA Cup means in 2012 is not born from sour grapes from an Arsenal fan after seven years of failure to secure a trophy. Nor is it Wengerite propaganda trying to dress up third and fourth place as trophies in themselves. To paraphrase Dean Acheson’s quote on the decline of British imperial power, since the turn of the century the FA Cup is the trophy that has lost an empire and has not yet found a role in the world. However, don’t mistake this as an argument that it is right to see winning a trophy as meaningless – because, equally, you would have to be an extremely one-eyed Arsenal fan to see coming third or fourth in order merely to secure a source of revenue as a better state of affairs than actually winning something - which is, lest we forget, what the game is actually supposed to be about.

I therefore hark back to an article I wrote in January, 2009 to reiterate what I still believe to be the solution to the problem at hand. It’s rather spirit-crushing to think that, in what is nearly three and a half years since writing that article, Arsenal are in almost exactly the same position as they were then – not seriously challenging for any trophy, while trying to scrape a third/fourth spot to retain a source of Champions League revenue for the following season. This season, the business model followed by Arsenal might well be scuppered by a cruel irony: the side may well fulfil its mission to finish fourth but end up evicted from their perennial Champions League spot by a side finishing sixth, having their worst domestic season for many a year, but actually drawing on their vast knowledge of knowing how to win things to steal the Champions League and, with it, our annual superficial ‘trophy’ of Champions League qualification. In order to change the clubs’ mind-set on how to approach winning things, the football authorities need to ensure that actually winning trophies makes financial sense and counts for something. The sensible solution to this would be to ensure that all nations with four slots in the Champions League have to hand one over to their national Cup-winners. Until they do, modern football will continue to reward mediocrity. The Americans have a saying – ‘people only remember the winners, no-one remembers the guy who comes second’. Unfortunately, the hierarchy of modern football in most instances remembers those who finish second, third and fourth over those who have actually won something.

Follow me on Twitter@robert_exley.