Football – it’s a business like any other, and has always been a business like any other, hasn’t it? Football-supporting is like a romanticised consumer choice, isn’t it? Though everyone protests that their allegiances are wholly different to their choice of, say, what supermarket they shop in, the reality is that it’s the same free-market choice to consume at one place rather than another, surely? No? What, in essence makes Football different then? Well, football’s exceptionalism comes from the fact that, in contrast to the ‘business like any other’ platitude that often does the rounds, the roots of football are far more collectivist in their origin than media coverage on the matter would have you believe.

Today’s players may kiss the badge to show their devotion to the cause, but before 1961 there had been little need for badge-kissing antics, as the players were going nowhere without their club’s say-so, regardless of whether their contracts had expired or not. Their wage was also capped, meaning that being an oligarch-owner of a football club looking to poach the top talent of your rivals by merely waving your wallet around would have been utterly pointless. The downside to this system, illustrated by Gary Imlach’s book ‘My Father and Other Working Class Heroes’, was that players were treated like chattels by their clubs and, rightly, this system was overturned by a high court in 1963.

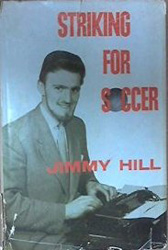

The maximum wage had been abolished by the Football League without recourse to legal action two years earlier (though under duress of a strike brought by Jimmy Hill’s PFA). Prior to 1961, footballers mainly earned less than the spectators who watched them, and the absurdity of this scenario was highlighted by Bolton Wanderers’ left-back, Tommy Banks, at a PFA meeting, where a delegate from Bury FC argued against strike action because his father, a miner, didn't earn as much as he did. In response, Banks – an ex-miner himself - had stated: ‘I'd like to tell your father that I know the pits are a tough life. But there won't be 30,000 people watching him mine coal on Monday morning’ and then, pointing to Blackpool’s Stanley Matthews, added ‘there will be 30,000 watching me trying to stop Brother Matthews here’.

However unfair Football’s maximum wage had been, uncapped salaries in football in the years since haven’t been entirely without consequence for the game, particularly so after the foundation of the Premiership in 1992, where the balance of power has swung full circle. In the two decades which followed the formation of the Premiership, players’ wages grew by as much as 1508% (as a comparator for the rest of society the average had been 186%), with the knock-on effect being that, by 2011, it was reported that only eight of the Premiership’s twenty clubs actually recorded a profit.

Global management consulting firm A.T Kearney even goes as far as to claim that, since the introduction of the Bosman rule in 1995, football clubs have in essence become mere vessels for transporting football’s income to footballers and their agents. A meeting between Middlesbrough forward Wilf Mannion and baseball legend Babe Ruth, after a game at Highbury in 1939, had allegedly led to Ruth calling English footballers ‘bloody idiots’ when Mannion informed him that, despite playing in front of a 70,000 crowd, the players were on a maximum of £8 a week. Seventy-five years on, many observers of North American sports may possibly come to a similar conclusion regarding English football’s wage structure.

Salary caps - placed on the clubs rather than the players - do frequently operate in North American sports. However, unlike English football’s maximum wage era, most major North American sports stars are still earning millionaire salaries in spite of the presence of a salary cap, in large part due to the fact that the cap is annually adjusted with the player’s unions playing an active part in setting the cap figure. For a land where the unfettered market has always reigned supreme and still to some extent fears the ‘reds under the bed’, the Gridiron game – America’s national winter sport - has been described by some social commentators as following a ‘socialist’ model.

Salary caps are also present in Australian sports, as well as in both codes of English rugby. Almost always, all of these sports have a healthier competitive balance when compared with the English Premiership. Prior to the abolition of football’s maximum wage in 1961, the most successful side in English football since the maximum wage was implemented in 1901 was Arsenal, who had seven titles to their name. The next best two sides were Manchester United and Liverpool. However, these three clubs were among seventeen different title-winners over forty-nine competitive seasons. Their collective share of league titles over this period had been 32.6%. Since the abolition of the maximum wage, however that share has nearly doubled to 64.2%.

This imbalance accelerated much further when the Premiership was formed, as throughout the 1970s and 80s, though Liverpool had often occupied the top spot at the end of the season, the pacemaker sides were rarely the usual suspects – with runners-up ranging from smaller sides such as Ipswich, QPR and Watford, to big-city clubs such as Arsenal, Everton and Manchester United. Today, in contrast, the top five positions are occupied by almost always (give or take the odd surprise like Manchester United’s collapse under David Moyes last season) the exact same sides, year in year out.

Similarly, at the other end of the table, the bottom three of the Premiership usually have at least one side which came up the previous season heading back down again. If you, and a group of your friends with any modicum of football knowledge, sat down at the start of the season to predict the top four sides and the three to be relegated, in no particular order, for the season ahead, there is a strong likelihood that, come May, most of you would get at least four (possibly five) correct. Carrying out the same prediction twenty years earlier, however, would have undoubtedly been a harder task, which implies that Premiership football is on its way to becoming as pre-determined as that other great all-American sport - professional wrestling - only minus the artistic licence of a WWE scriptwriter.

How has this come about? Isn’t this just meritocratic with the top five sides just simply better than the rest? Well, to a degree; however, how football’s wealth has come to be distributed over the last three decades needs to be taken into account. Today, football’s primary income source is TV revenue. The Premiership now reaps £5.5 billion in global TV rights, which is distributed unequally between twenty sides – with a club’s position in the league and how many times their games are televised over a year accounting for the difference in revenue between the sides.

In contrast, back in 1979 the Football League’s TV deal reaped just £2.2 million from the BBC and ITV collectively, which was to be shared out equally between all ninety-two member clubs, leaving not a particularly great amount of revenue to be reaped by each individual club. The main income-generator for clubs therefore would come from gate-receipts, giving the attending fan a considerable amount of power (power which has now been transferred to the TV companies and the armchair fan, both home and abroad). Also, back in the early 1980s, all gate-receipts from Football League fixtures were split evenly between the home and away sides, with a 4% levy which accrued to the Football League and which was re-distributed among all ninety-two member clubs equally.

Since the start of the 1983/84 season however, all gate-receipts have been kept by the home side. The effect of this is illustrated by a quote from The Times Newspaper in February 1983, which highlighted that, under the old arrangement ‘If Manchester United was to play Coventry at Highfield Road 21 times, Manchester United would receive £60,000, but if Coventry City played Manchester United at Old Trafford the same number of times, Coventry City would receive £250,000’. The abolition of gate-sharing has, without a doubt, empowered the Manchester Uniteds of football over the Coventrys. There had also been no significant sponsorship deals prior to Liverpool’s deal with Hitachi in 1979.

Thirty-five years on, almost every club has a sponsorship deal of sorts, but not all clubs are equally attractive to the sponsors. Manchester United have several official partnerships worth a seven-figure sum, but how many companies would wave a seven-figure before Burnley or Crystal Palace simply to become their official savoury-snack partner? Ultimately, this disparity of income creates a competitive imbalance within the league to the extent that small provincial sides like Southampton and Swansea City are considered to be exceeding all expectations if they manage to reach eighth in the Premiership. However it wasn’t so long ago that equally small provincial sides like Nottingham Forest, Derby County and Ipswich Town were actually winning League titles and European competitions.

You may be asking at this point how this affects us, being that this is an Arsenal site, we being one of the bigger clubs and, aside from Wembley last May, seemingly unable to win a pot for love nor money. Well, such is the absurdity of football today that, arguably, Arsenal, Liverpool and Manchester United are the ‘underdogs’ for merely not having a sugar daddy to fund them beyond their means as Chelsea and Manchester City have. Or, you could look at it another way – that Chelsea and Manchester City are actually the modern ‘underdog’, albeit one that’s grossly pumped up on financial steroids in order to compete with and overtake the aristocrats of the game who have bigger fan-bases and greater independent financial means.

It’s easy to forget that the Premiership’s competitive imbalance actually pre-dated Abramovich’s arrival in 2003, where the only three Premiership winners by this point were England’s most supported and richest side (Manchester United), the most supported side in the richest part of England (Arsenal) and another side funded excessively beyond their means (Blackburn Rovers). Thirty-five years ago, a minnow side without a significant history could rise from the second tier to win the league and back-to-back European Cups purely on the strength of one man and his management skills (Brian Clough). In contrast with today, where an English club side without a significant history rises up to the Champions League elite, it does so only on the strength of one man’s wallet (Roman Abramovich/Sheik Mansoor). And this is before we even take the Champions League qualification factor into account.

The financial difference between qualifying for the first round of the Champions League and qualifying for the first round of the Europa League can be as much as £20 million; hence the reason why Arsène Wenger (regardless of any tactical deficiencies which I’m sure you’ll argue about among yourselves till the cows come home) prefers to see fourth place as a ‘trophy’ over a real one made of silver with handles like the League Cup and FA Cup, which of themselves offer much less financially to the victors. Even sides at the foot of the Premiership would prefer to finish seventeenth in the table than be relegated and win either of these trophies.

This development has redefined ‘success’ in Football as something much more benign, with the expectation that fans will applaud the attainment of a mere revenue-stream that comes with finishing places in the Premiership over that of actually winning a trophy. After all, if Arsenal had won the FA Cup last season and finished fifth, the bean-counters would have effectively deemed it a season of ‘failure’, in comparison with the ‘success’ of the nine trophy-less seasons which preceded it. And it has been this benign form of ‘success’ which has effectively kept Arsène Wenger in his job for the last few seasons. What strikes me most about the changes in football which have facilitated this rise of ‘benign success’ however is how little they were actually fuelled by public demand.

For example, often when perusing the comments section of my previous articles, it’s notable the number of times people have bemoaned the extension of Champions League qualification beyond the domestic title-winners, as it used to be up until 1997, and even called for a return of the straight knock-out competition of the European Champions Cup format pre-1991. In my own opinion, it’s doubtful whether this would be a great improvement on the current format but it does remind me that this was a development which occurred with practically nothing in the way of public demand.

Similarly, no football fans were crying out for the creation of a breakaway Premier League back in the early 1990s. Both of these developments came about as a result of the owners of the big clubs threatening to break away from the established set-up, if the powers that be didn’t appease their money-making urges. The concerns of advertisers, television companies and football club CEOs took primacy over that of the fans – who, if nothing else, are football’s ‘consumer base’ (name me one other industry which so brazenly disregards the wishes of its own consumers in this fashion?).

And yet, up until three decades previously, so anti-commercial was the ethos of English football, that there actually was a rule against profits being made in the English game. In 1912 the FA enacted Rule 34, which restricted the dividends that football clubs could pay out to shareholders to just 5% of the share’s face-value. Rule 34 also restricted what could happen to the assets of a club were it to face a winding-up order; it disallowed a club owner’s ability to liquidate a football club and sell off its ground for a profit, as well as preventing football club directors from receiving a salary from their clubs.