I’m struggling to care what happens to Arsenal’s season from here on out. After last Wednesday night’s abysmal Champions League defeat to Monaco, I’m honestly struggling to care. If that sounds snide or petulant, it’s not meant to be. I’m a passionate Arsenal fan. I have no particular tendency to froth at the mouth after defeats and I certainly don’t identify as a WOB – one of the elite ‘Wenger Out Brigade’, for anyone not acquainted with the laughable tribalism now dividing the Arsenal fan-base. Nevertheless, my current feeling towards my club is one of sapping, gruelling apathy. I’m struggling, struggling to care.

In a footballing sense, the main reason for my lethargic struggle is repetition. A repetitive tactical approach, first and foremost, was the reason for Arsenal losing last Wednesday’s match in the manner they did. The Gunners started by trying to play open, attacking football against a notoriously resolute Monaco side. One midfield dispossession later, and they were one down. Arsenal then tried to play even more open, attacking football. One more counterattack later, and they were two down. Eventually, after a period of impotent but still rather open attacking, Arsène Wenger’s side pulled one back through a brilliant individual finish by Alex Oxlade-Chamberlain. At that point, firmly back in the two-legged tie with only added time to go, Arsenal went on to play – that’s right – open, attacking football. Another midfield dispossession. Another Monaco counterattack. Another away goal conceded. Game over.

If a dogged lack of variation from open, attacking football sounds like a familiar criticism of Arsenal, that’s because it is. It was the reason that we conceded eight soul-destroying goals at Old Trafford in 2011, when the second string went at Alex Ferguson’s Red Devils with all the futile offensive bluster of a First World War light cavalry division – and were shredded accordingly. It was the reason we lost six-three, five-one and six-nil last season to Manchester City, Liverpool and Chelsea respectively; in all of those games, but in the last one especially, Arsenal seemed to be trapped inside some sort of terrifying nihilistic vortex, compelled to scamper onward without purpose while perpetually prohibited from defending, organising or even regrouping as goal after goal slammed mercilessly into Wojciech Szczęsny’s net.

More recently, our lack of variation was the reason that we drew three-all with Anderlecht in November of last year, the team found out for bombing forward despite being three goals to the good; it was also the reason we lost two-one to Louis Van Gaal’s subdued but shrewd Manchester United a few weeks later, caught twice on the counter having spent the entire game galloping toward inevitable dispossession on the edge of their penalty area. I could go on, but the repetition would probably put you off this article. Thankfully, that nicely exemplifies quite how disconcerting said repetition has become.

The tactical inflexibility of the side is surely the basis of the increasingly predictable nature of our league campaigns. With last year’s triumphant FA Cup win a welcome anomaly – let’s not mention the final’s opening ten minutes – the seasonal pattern is striking; Arsenal go out of the cups early on to weaker sides; Arsenal go out of the Champions League at the Round of 16; Arsenal put a half-decent run of results together in response; Arsenal finish fourth – and it’s on to the next season. Within this general pattern, there are the same old distinctive failings year in, year out. Arsenal lose to Stoke away. Arsenal drop points to the promoted sides. Arsenal inevitably lose every single possible meeting with José Mourinho’s Chelsea, threatening to subvert the very laws of probability which govern our human understanding of the cosmos.

The consequence of all this? Following Arsenal has become boring. I should qualify. Attacking football has not become boring; it often produces scintillating moves, wonderful skills and brilliant goals on the pitch. The players employed by the club have not become boring; I am well aware that they are some of the best in the world. What has become boring is the process of following Arsenal’s results all year round, of actually investing oneself in the team’s fate; the enduring tactical inflexibility, the recurring mistakes, the Groundhog Day season – the monotony of it all is enough to bore the most rabid, red-and-white-blooded, cannon-on-his-chest Arsenal fan to exhausted, sleepy tears.

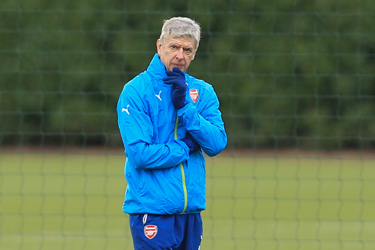

Arsène Wenger is obviously accountable for this. Arsène Wenger is the only man responsible for team tactics and subsequent results. Arsène Wenger would probably tell me to shove my opinions (not verbatim) were he to read this, seeing as I’ve never managed a game of football in my life. All the same, the footballing monotony at Arsenal is self-evident.

At this point, I fully expect some readers to have become enraged by my self-proclaimed apathy. After all, following a football team is not just about results, campaigns and silverware. It’s about fervour, it’s about sociability, it’s about singing and making a racket and creating an atmosphere with ardent supporters. Unfortunately – and this, I feel, is seriously tragic – Arsène Wenger has presided over an era of change for Arsenal which has seen even these fundamentals of support fade away. The repetitive football hasn’t helped matters, but nor has it been the main factor in this. The main factor has been the off-field transformation of the club, as overseen by the manager and the board.

As it stands, the Emirates is a sterile ground. It’s sterile because it is, above all, a corporate space. Its name is corporate. Its logos are corporate. The bloated swathe of ‘hospitality’ sheen that separates bottom from top tier is corporate. The name and logos suck personality from the ground, while the segregated middle section actively sucks away at the noise of the supporters, dissipating the songs, chants and shouts that should ideally unite the place as a whole.

Naming rights, advertising deals and hyper-expensive function rooms all make the club money, of course. The move from Highbury to the Emirates was always intended to generate massive new income for the club; this is what Arsène meant when, after the announcement of stadium funding in 2004, he said ‘relocating to a new stadium is a necessity as it will enable us to become one of the biggest clubs in the world’. Still, all this money – plus that generated by the 22,000-capacity increase on Highbury – has not stopped ticket prices rising almost every season, including a 3% rise at the beginning of the current campaign. This has, necessarily, made the crowd itself more corporate. All of these issues combined have, equally necessarily, ensured that the ground is now a generally boring place to be.

Arsène Wenger is by no means wholly accountable for this. Arsenal’s various board members over the last decade should accept the vast majority of the responsibility. However, as Arsène’s statement from 2004 (and much else since) suggests, he did back the move. He consulted with the board. He wanted Arsenal to make a massive financial leap forward, to become ‘one of the biggest clubs in the world’. As such, he may not have designed the Emirates, he may not have done the commercial deals, but he was certainly an important part of the move from Highbury – one way or another, he’ll be remembered for it.

If my criticism feels as if it’s gradually turned snider and more petulant then, again, I must reiterate, it’s not meant to be. I might be apathetic, but I’m still a fan; unlike some of the waffling, egotistical, News of the World-made prats who regularly pass uninvited comment on my club, I would genuinely like to contribute something constructive. For me, then, the overarching fix for the football seems relatively clear; Arsène must be more changeable, more adaptable and more radical – just as he was when, a couple of decades ago, he insouciantly revolutionised the English game. Coincidentally, a radically-minded Arsène might also be the fix for the Emirates itself.

In his last few years as Arsenal manager, were Arsène to give the board his input on how to improve the ground, his legacy in North London might be acclaimed for more than just the glory years of old; likewise, the years of monotony might be quickly forgotten. He contributed to a change of ground before. Change is needed again.

The club’s corporate commitments are not, realistically, going to be abandoned; naming rights, advertising deals and function rooms are all part of the modern business of sport. Nonetheless, they need not define a football club. Cliché or not, it is essentially true that without its supporters, Arsenal is nothing; commercial activities are entirely meaningless if even the most loyal fans are too apathetic to push through the turnstiles, to pay to watch games and to make each game a spectacle worth watching. Therefore, whether it’s by lowering ticket prices all round, increasing the ground’s capacity and lowering prices proportionally, backing safe standing to the same effect or some other, completely different scheme, Arsène and those running Arsenal must find a way of maintaining a diverse and involved crowd – they must find a way of making the club compelling once more.

If fantastic new football follows, that would be more than welcome. Either way, an exciting future for Arsenal depends on Arsène Wenger helping to rectify the sterile failings of past and present. Keep on replicating them, and it’s his legacy at stake.