Mikel Arteta’s squad may have returned to light training in a bid to bring a semblance of normality during lockdown – but how would they have fared around 130 years ago when a trip to the earth’s molten core was deemed more preferable than a visit to Royal Arsenal’s Manor Ground?

Read on for a wonderful evocation of that era from renowned author and passionate Arsenal supporter Jon Spurling in an excerpt taken from his superb book Rebels For The Cause.

‘A journey to the molten interior of the earth’s core would be rather more pleasant and comfortable an experience than our forthcoming visit to the Royal Arsenal…’

The Derby Post, January 15, 1891

The Derby Post’s view on Arsenal’s distant forebears is a typical one from an era when any team south of Watford was invariably dubbed ‘southern softies’.

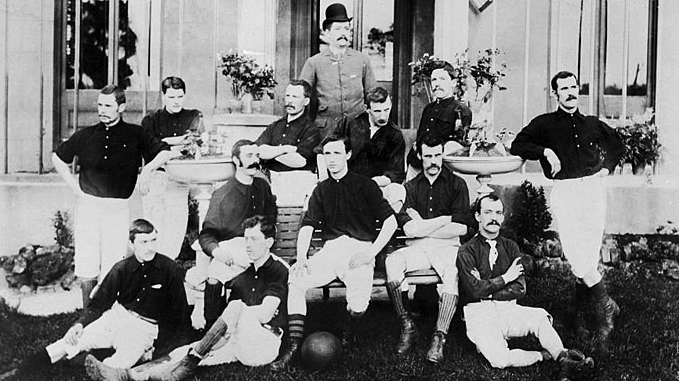

Not so Royal Arsenal, the roughest, toughest crew of their time apparently. After 90 minutes of mortal combat against the likes of Morris Bates [Bates is shown behind the bench, third from the right, looking down in the picture above], John Julian and Jimmy Charteris, the battered opposition would limp home, recounting tales of carnage in Kentish fields.

Ten years later, perceptions of the newly titled Woolwich Arsenal had barely changed. The entire Second Division winced at having to venture south, such was the dread engendered by a trip to the Manor Ground in Plumstead, as the club’s infamy grew in the late 1880s and into the 1890s.

To many, it seems entirely appropriate that the only footballing fatality of 1896 happened to be Woolwich Arsenal’s own Joe Powell, whose broken arm became infected after a clash with Kettering Town.

The Woolwich Boys became everyone’s least favourite team

The fact Woolwich Arsenal were distinctly mediocre – was some consolation for their rivals. Years of plugging away in Kent meant the club missed out on the gravy train of talent which flowed north to sides such as Wolves and Sunderland.

Even when the Royals had attempted to play decent football at their first ground, the crater-ridden surface at Plumstead Common scuppered their efforts – the Highbury mud flats which almost derailed their 1989 title challenge were like a billiard table compared to the Common’s pock-marked surface – as late 19th army manoeuvres resulted in the pitch littered with holes, ruts and hoof marks as well as the damage from army motors driven over the sorry surface.

It is also worth remembering there were no crossbars – tape was used instead. It was the latest comical installment in a long-running saga.

Rough and ready Dial Square and the health hazard of the open sewer

The official story goes that Dial Square had played their first match against the Eastern Wanderers on the Isle of Dogs. Resplendent in a variety of multi-coloured knickerbockers, the boys won 6-0 – but were hardly enamoured when the ball kept landing in the open sewer which ran behind the goal. Club secretary Elijah Watkins reported that players had to scrape off the ‘mud’, as he tactfully put it, before the game could restart. Little wonder the local sanitary inspector, the aptly-named Mr Fowler, deemed the pitch ‘an obvious health hazard’.

Heading the heavy old-style football was one thing, being splattered with human excrement was quite another. Ironically, the club’s sewer-related problems didn’t end there. All this contributed to the fact that, despite their regal name, Royal Arsenal were a rough and ready outfit.

The inhospitable Manor Ground at the ‘end of the earth’

It was hoped, by club officials and opposition alike, that the move to the Manor Ground in 1893 would benefit everyone. In time, the team gained from the improved facilities, the existence of stands and terraces, and cheaper rent.

Visiting teams looked forward to the dream of parading their skills on a croquet lawn surface and in a generally more pleasant atmosphere.

But after a couple of months, the Manor Ground had become everyone inch as inhospitable as Plumstead Common had been. Yet there were several advantages to being regarded, in the words of the Liverpool Tribune, as the ‘team who played at the end of the earth.’

Teams such as Newcastle and Rotherham dreaded the trek south especially as rail travel was so slow and unreliable at the time. On top of a seemingly endless journey into London, there was an uncomfortable 40-minute ride from Cannon Street Station to Plumstead in an overcrowded steam train, often filled with heckling home fans. Overnight accommodation was also a real pain, particularly as no self-respecting hotelier wanted a bunch of working class oiks wrecking the joint.

So when teams arrived in Woolwich, they were usually bad tempered and in no fit state to play football. Little wonder that during the club’s 13-year stay in Division Two, home form was excellent.

Rancid and grotesque smells at the Manor Ground

The Manor Ground also acquired its own unique notoriety thanks to the tactical deployment of the huge engineering works nearby and the proximity of the main liquid waste disposal for the whole of south London.

The grotesque vision of the factory, belching out noxious compounds meant that a thick mist and rancid smell hung in the air. The sewer pipe provided opportunists with a chance to watch the team for free, though occasional leaks of raw effluent meant that Arsenal games often stank – both literally and metaphorically.

This is an excerpt taken from Jon Spurling’s book Rebels For The Cause. Buy it here.

Follow passionate Arsenal supporter Jon on Twitter