The most common defence of Arsène Wenger’s management relies on arguments relating to ‘relative spend’ - how much he spends on players’ wages and transfer fees compared with the other biggest clubs in the League. It is often represented as ‘Holy Gospel’ and, it is argued, it is a ‘fact’ that Wenger overachieves. Actually it’s an interpretation, as it assigns a subjective significance to this factor, but nonetheless, it seems on the surface like a plausible approach.

I want to say firstly that this article is not intended to undermine our recent FA Cup triumph. I was the second to comment on this site by saying how things have improved and pointing out our great prospects for the future. I waited for the end of a five-year period from 2009 to complete the analysis that this work involves.

The focus of my article, then, is to examine a factor which is given very little attention during the debates regarding relative spend - the strength of the Premier League. I accept the reasoning for the ‘relative spend’ argument before 2009 but, as we will see, it fails to apply thereafter.

To do this, I have applied a formula to club’s performances in the Champions League - ten points for reaching the last sixteen, 30 points for the Quarter Finals, 60 points for the Semi-Finals and 100 points for the Final. It is broken up into two key periods, from 2004-2009, a golden era for English clubs, followed by 2009-2014, a period of decline. As it would take up far too much space to look at each club’s performances for each season I’m going to look at English clubs’ overall totals.

Period 1

04/05 Season Total: 180 points

05/06 Season Total: 130 points

06/07 Season Total: 230 points

07/08 Season Total: 290 points

08/09 Season Total: 250 points

Period Total: 1080 points

Period 2

09/10 Season Total: 70 points

10/11 Season Total: 170 points

11/12 Season Total: 110 points

12/13 Season Total: 20 points

13/14 Season Total: 110 points

Period Total: 480 points

That, clearly, is some fall in performance. Another analytical consideration to make is that Chelsea were incredibly lucky to win the 2012 competition. Their anti-football win was the equivalent of Wimbledon winning the 1988 FA Cup. That they lost 4-0 in the Super Cup to Atletico shortly afterwards and then went out in the following season’s group stages, gives a more realistic assessment of their recent standard.

Manchester United too were lucky to have a relatively easy run of games to reach the 2011 final, and they were easily beaten by Barcelona. Of course, had these two competition runs been more reflective of those teams’ standing, the Period Total would be even lower.

The first thing to consider is why this is. Is it just because the German and Bundesliga teams have improved so much? There may be an element of that, but it seems a factor of secondary importance. Barcelona, for example, were still under the leadership of Pep Guardiola before 2009, but English clubs had the better of them. It should also be noted that the performances of French and Italian teams has been markedly weaker in the second period. The weakening of teams such as AC Milan is attested well enough already.

No, when one looks at how the Premier League elite dominated Europe in the 2004-2009 period, comparing how their teams changed is the most important factor. Manchester United had Paul Scholes and Ryan Giggs pretty much at their peak for this time, and they had the ‘jewel in the crown’ that was Cristiano Ronaldo. Since they sold him, their club has been in decline; even their fans were bemoaning by the 2011-12 Season that they had ‘the weakest United team for 25 years’.

Chelsea likewise saw their elite squad begin to age. Interestingly, the peak age for player performance is considered 25-28; the average age of each team in the 2008 Chelsea - United final was 28! Both teams clearly needed a transition that involved major squad rebuilding, and it is still taking a great deal of time. In no way does the Chelsea side of the last few years compare to the one that had Lampard, Terry and Drogba (etc.) at their peak.

Arsenal’s decline is not difficult to map out since 2009. Major operating losses of £20-30m per season thanks to the wages of the ‘deadwood’ meant the need to sell first-team stars where property sales couldn’t paper over the cracks. Losing so many key players in this period of course damaged the team, though in my view we are now seeing a great rebuilding of the squad.

Liverpool’s fall is hardly something that needs recounting. But it takes us onto an interesting point. Their ‘successors’, Manchester City, have, given three attempts, only managed to reach the last sixteen once. This brings us back to my main contention, the notion that in the last few years it would have been necessary to spend on the scale of Chelsea and Manchester City hardly holds true. Do some people seriously believe it would cost hundreds of millions to do better than teams that can barely scrape through the group stages?

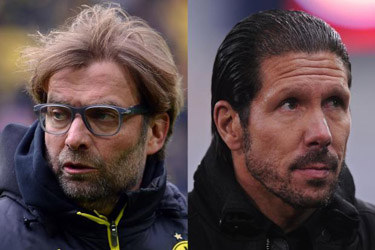

Teams like Dortmund and Atletico win because they view it in different terms. It is how it is spent, not how much. For example, it would have cost £4 million to buy Mark Schwarzer a few years ago; not much on paper but in practice it would probably have represented an overall squad improvement of several tiers compared to the woeful liability that was Almunia.

Money spent is also not necessarily spent well; in order to compete, a team must have a complete team or squad. Chelsea can’t compete with £50 million signing Fernando Torres up front. Look at how Manchester City’s strong team was continuously let down by the weakness in the centre back position earlier this season.

Whether or not people choose to factor in the decline of Premier League clubs when looking at relative spend is up to them. However, the continuing rebuilding of the league’s biggest teams gives hope to Arsenal, as the first to recover could be the one to establish domestic dominance. The right transfer activity this summer could be the cornerstone of such success for Arsenal.