In 1971, Arsenal won the double by beating a Liverpool side who at this point had spent five years trophy-less. Their barren spell was to extend for another season when, in their final fixture at Highbury in May, 1972, they had failed to secure the two points required to take the league title back to Anfield. The Arsenal side of ’71 were seen as a well-drilled machine that would grind out results, along with having players such as Charlie George, Ray Kennedy, Pat Rice, Eddie Kelly and John Radford, who were all under the age of 25. Many assumed in 1971 that this Arsenal side would have the whole of the 1970s at their feet. However, by the end of the decade it was, Liverpool that were to be the red machine that dominated English football. The year that was to see the two sides start to veer in different directions was to be the 1972/73 season.

It was a season that was to start well for the Arsenal, who remained unbeaten in their first seven matches, until losing their first game at Newcastle 1-2 in early September. Two defeats were to follow in October, followed by the signing of Jeff Blockley for £200,000 from Coventry, intended as a long-term replacement for Frank McLintock. Although Blockley had at this point had gained an England call-up, he would later be referred to by Bertie Mee as his greatest mistake in football management. In his autobiography, Peter Storey said of Blockley that ‘he was supposed to be a good player, although I never saw any startling evidence’. By the end of October, Arsenal were still within one point of Liverpool at the top of the table. However, there followed a 0-2 home defeat against Coventry.

According to Phil Soar and Martin Tyler’s official history, in 1972/73 the Arsenal had also attempted a tactical change of style from what the football world had become accustomed to with North London’s finest. Known up until this point for their ‘no frills’ approach to football with a great deal of criticism from the neutrals, as well as reflecting on their elimination from the European Cup at the hands of Ajax a season earlier, ‘Mee’s answer was to attempt to turn Arsenal into the total footballers of Holland…but Arsenal’s flirtation with a style alien to their successful long-ball game, and equally unsuited to the consistently tough demands of English football was brief’. Mee’s u-turn came as a result of exiting the League Cup through a 0-3 home defeat to Norwich. The following Saturday, this was followed by a 0-5 trouncing at the Baseball Ground at the hands of reigning Champions, Derby County..

Arsenal however reverted to type for Leeds Utd’s visit to Highbury the following week with positive results, as Arsenal ran out 2-1 winners. The following week Arsenal also beat Tottenham 2-1 at White Hart Lane and there followed a run of fifteen games unbeaten in all competitions. The main highlight within this unbeaten run had been a 2-0 victory over title-rivals Liverpool at Anfield in early February, which saw Arsenal take the top spot from the Merseysiders.. However, pole-position was to be lost two weeks later at the hands of Don Howe’s West Brom, who were fighting a relegation battle at the bottom end of the table. Arsenal, however, had managed to keep the pressure on Liverpool with four straight wins, which included a 2-1 away win over Man City, followed by a 1-0 win over Crystal Palace 48 hours later. On the day of the 1973 Grand National (which the Racing historians among you will know was won by Red Rum), Liverpool had kicked off early against Tottenham at Anfield, drawing 1-1, giving Arsenal advantage in the title race, but a 0-1 defeat by Derby at home put Liverpool back in control of their destiny again with a game in hand.

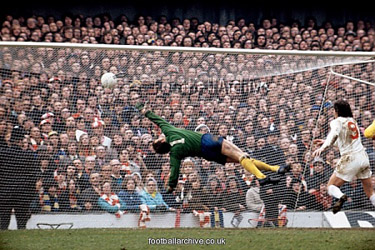

Arsenal, however, were also putting together a good FA Cup run, sensing a part of history to be achieved in either another double and/or becoming the first side of the twentieth century to reach three successive finals. Drawn against Chelsea in the Quarter Final, an epic tie ensued with a 2-2 draw at Stamford Bridge. The replay at Highbury four days later, in front of an attendance of 62,746, saw Chelsea take the lead through Peter Houseman before a controversial penalty decision, where George Armstrong had been brought down by Alan Hudson.

Initially, the referee, Norman Burtenshaw, who also took charge of the 1971 FA Cup Final, had deemed the foul to be outside of the box and awarded a free kick. The Arsenal players in response had so vehemently protested that the foul took place inside the eighteen-yard box that they had convinced the referee to consult with his linesman. The man on line, as video footage would subsequently prove, rightly called for a penalty which was duly awarded. Alan Ball had coolly converted to equalise, followed then by a second-half winner from Ray Kennedy heading superbly past reserve keeper John Phillips in the Chelsea goal from a Bob McNab cross in front of the North Bank, putting Arsenal through to their third successive semi-final.

Against second-tier Sunderland at Hillsborough, Arsenal were red-hot favourites to reach another Cup Final. However, a Jeff Blockley-induced nightmare was to follow, as Arsenal crashed to a 1-2 defeat. The fall-out from the semi-final defeat was an inability to put together a winning run for the remaining few games. Three consecutive draws saw a four-point deficit widen between Arsenal and Liverpool by the final Saturday, even though Arsenal had a game in hand. Arsenal kept the pressure on with a 2-1 away win over West Ham, but Liverpool’s 0-0 draw with Leicester that day saw the title finally head back to Anfield after a seven-year wait.

It was a close-run season for the Arsenal. However, rather than a springboard for better things for Bertie Mee’s side, it was the start of an irreversible decline for his tenure. Despite coming second in the league, they were denied a place in Europe to League Cup winners Tottenham Hotspur in the UEFA Cup as only one club per English City was permitted entry. This rule had previously been enforced by UEFA with regard to the days when the competition was referred to as the Inter-Cities Fairs Cup. UEFA ditched the rule when rebranding the trophy as the UEFA Cup in 1971; however, the Football League still retained the criteria of one club per city for qualification for the 1973/74 season.

In the close season of 1973, Bertie Mee had also sold Frank McLintock to QPR, which turned out to be a gross error on Mee’s part, as Frank carried on playing for another four years in the top flight. On the subject of Frank’s departure to South West London, according to Soar and Tyler’s official history, ‘the news hit a nervous dressing room like a bombshell. Not only did McLintock feel his days at the top were far from over, but his team mates still regarded the inspirational Scot as the best skipper in the league, and capable of doing a first-rate job in defence’. Indeed, Frank nearly lead the Rs to a title victory in 1975/76, but again had to make do with finishing as runners-up to a Liverpool side winning the title again in their final fixture of the season.

Post-1971, there had also been an issue surrounding Arsenal’s wage structure. Peter Storey in his autobiography stated that when Alan Ball transferred to Arsenal ‘the size of his wage packet was a source of jealousy in the dressing room and none of us was impressed when his dad, Alan Ball senior, remarked that: ‘Alan didn’t want to move South but Arsenal guaranteed him £12,500 a year’. Also, both Charlie George and Eddie Kelly ended up on the transfer list as both felt that they were inadequately rewarded in comparison to senior players who benefitted from the club’s loyalty payments. Consequently, both had left Arsenal by the middle of the decade.

Bertie Mee also proved to be less than astute in the transfer market. He took issue with Ray Kennedy being a little overweight, as well as his loss of form since the double year, and decided to move him on, becoming Bill Shankly’s leaving present to Liverpool in 1974. His successor, Bob Paisley, converted him into a midfielder and there followed another three Championship medals for Ray by the close of the decade, as well as two European Cup-winners medals. In contrast, Bertie Mee’s Arsenal went into free-fall over the next few seasons. Kennedy’s replacement had been Brian Kidd, signed from a recently-relegated Manchester United in 1974. He spent two seasons at Highbury; his first was a successful one, but, as Peter Storey stated in his autobiography, ‘I got the impression that Kiddo never wanted to be at Arsenal; in his mind he was still a United player…I wasn’t surprised in the least when Kiddo jumped at the chance to return to Manchester, albeit with City rather than United’.

The relegation-form virus also seemed to have followed Kidd from Old Trafford to Highbury, as Arsenal finished 16th in 1974/75 and 17th in 1975/76, in both years entangled in a relegation survival battle along with Terry Neill’s Tottenham Hotspur, who eventually did go down in 1976/77 under his successor Keith Burkinshaw. These were Arsenal’s lowest finishes since Chapman’s arrival in 1925. However, the club’s direction was to change for the better when Bertie Mee announced he was to retire in 1976. His successor, fresh from resigning as Tottenham’s manager nine days earlier, was former player Terry Neil, who made the short journey down Seven Sisters Road to Highbury.

In Neill’s first season, Arsenal finished in eighth position. However, it was Don Howe’s return to Arsenal a year later that saw the club challenge for trophies once again. Arsenal were to become the most formidable domestic cup side of the late 1970s; however. a sustained title challenge was to remain elusive for another decade. And, as we’re all aware, as with the 1972/73 season, this title run-in also involved Liverpool, went down to the last day and was also to be settled at Anfield. The result however, was a very different one indeed.

*Follow me on Twitter@robert_exley